A Raymond Carver Poem

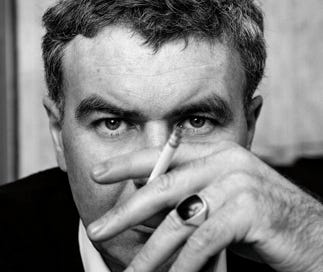

America produced many great writers after World War II. Many of them—as diverse as Arthur Miller, J.D. Salinger, Sylvia Plath, and Tennessee Williams—wrote about the underbelly of this period of prosperity. In their own way, each of them was animated by a sense of dislocation and what they perceived as the failure of the American Dream. Though not nearly as well-known, Raymond Carver (1938-1988) also wrote about those topics, in a personal, hard-nosed way.

To my mind, Carver is a true blue working-class fiction writer. George Orwell wrote passionately about the struggles of the urban poor, but he did so as an outsider, peering into their world with a journalistic intent and mindset. By contrast, Carver was born into poverty, and his personal background is always at the centre of his writing. His settings are threadbare and minimal, and his characters usually have a cynical make-do attitude. One paradox in his writing is that Carver seems to sentimentalise his characters’ rugged, simple lifestyles, while also criticising himself for his financial distress, his alcohol addiction, and his unrefined working-class attitudes.

When reading Carver’s books, one gets a sense of how limited his world is. It begins and ends in the Pacific Northwest, with the same recurring locations. The main available pastimes are talking, fishing, drinking, and driving about aimlessly. Yet, from these minutiae, he also draws out universal lessons about love, loneliness, parenthood, youth, and many other issues.

Today, I will share one Raymond Carver poem, “Luck”. It may not be one of his more famous poems, but it does sum up his philosophy and encapsulate his writing style. There is a self-reproachful tone coupled with inevitability and resignation. For this reason, I also find it sombre, resonant, and very evocative.

I was nine years old.

I had been around liquor

all my life. My friends

drank too, but they could handle it.

We’d take cigarettes, beer,

a couple of girls

and go out to the fort.

We’d act silly.

Sometimes you’d pretend

to pass out so the girls

could examine you.

They’d put their hands

down your pants while

you lay there trying

not to laugh, or else

they would lean back,

close their eyes, and

let you feel them all over.

Once at a party my dad

came to the back porch

to take a leak.

We could hear voices

over the record player,

see people standing around

laughing and drinking.

When my dad finished

he zipped up, stared a while

at the starry sky—it was

always starry then

on summer nights—

and went back inside.

The girls had to go home.

I slept all night in the fort

with my best friend.

We kissed on the lips

and touched each other.

I saw the stars fade

toward morning.

I saw a woman sleeping

on our lawn.

I looked up her dress,

then I had a beer

and a cigarette.

Friends, I thought this

was living.

Indoors, someone

had put out a cigarette

in a jar of mustard.

I had a straight shot

from the bottle, then a

a drink of warm collins mix,

then another whisky.

And though I went from room

to room, no one was home.

What luck, I thought.

Years later,

I still wanted to give up

friends, love, starry skies,

for a house where no one

was home, no one coming back,

and all I could drink.